'Toon Daddy©

Twelve Months in Vietnam as an RLO (commissioned officer) and combat helicopter pilot

As a preface to the following article, when I started my SubStack account, with no subscribers, it began with my first month in Vietnam as an RLO in 1968 and continued monthly for one year. As my subscriber base grew, many missed reading earlier stories helping to tie it all together. Wives of fellow pilots and friends suggested that I consolidate the files. This I have done in ‘Toon Daddy with minimal changes to the original monthly stories.

So, you may have read some of my stories but don’t have the entire historical context chronologically. Consolidated, this is as long as many books. There is an advantage, I am not a professional author, so no charge :-) No one is making you scroll further. Each monthly article can be read as a stand-alone.

I can only hope Taylor Sheridan will read it to pick up another storyline when Yellowstone goes off the air :-) Keven Costner will be out of work, so he could narrate to pick up some additional retirement income :-)

With CGI, a helicopter series now should be pretty cheap to produce. :-) This could be the modern-day version of the Black Sheep Squadron TV series that many of us grew up watching. :-) I only live a few miles from Taylor Sheridan (in Texas), so my consulting fees would be really really cheap :-)

1968 Vietnam as an RLO (March 1968) ©

Consolidated Articles Published June 10, 2023

Mar 23, 2022

(Real Live Officer i.e., Commissioned Officer)

Introduction:

I am trying to chronicle the most significant year in my life. By the end, hopefully, you will understand more of how I think and how that year directed the rest of my life. The acronym RLO stood for Real Live Officer. It was a term that the Warrant Officers, professional helicopter pilots, gave to the commissioned officers e.g., Lieutenants, Captains, Majors, etc. who also held the command positions in the 187th Assault Helicopter Company. It is a documentary of a twenty-one-year-old Lieutenant/helicopter pilot, still wet-behind-the-ears, entering the life of a combat leader in 1968 and leaving an old man of twenty-two. I am unsure how this story will piece together, so I will try to do this chronologically.

Originally, I was going to write a few paragraphs about each month; however, the more I wrote the more I remembered. The yearlong story is as long as many books. I will break it up by month and start posting it in smaller sections.

It is not a novel but an amalgam of events. It covers the heroes and a few (obfuscated) zeros. There is an awful lot of “I” in the narrative. Let’s face it; it is literary narcissism. How else or who else could have written it? It is my story.

I am dealing with memories that are over fifty years old. After writing a couple of paragraphs, I’d wake up in the middle of the night with something else to add. I kept writing.

If there are any 187th unit fact checkers reading, regardless of its accuracy, when something happened, was it in June or July, etc., the events covered did happen. Except for a couple of documented third-party events, they all happened to me or were on my watch as section leader, assistant platoon leader, platoon leader, or Air Mission Commander.

I’ve tried to minimize some of the personnel identities because many are still alive. Some would take issue with my comments or recollections. Consequently, there are negative events covered where I will obfuscate the names of some of the actual participants.

The story is not being written for other pilots or Vietnam participants per se, but it is written for the families and friends who missed out on our unbreakable bonds of brotherhood. There is also a series of six stories on my subStack library that covered my early years prior to combat in Vietnam.

Each generation has its unique heroes. In World War I it was the Sopwith Camel pilots dueling with the Red Baron as aviation warfare began.

In World War II it was the Spitfire crews determining the outcome of the Battle of Britain. Or as Sir Winston Churchill so eloquently stated, “Never was so much owed by so many to so few.”

Vietnam, aka The Helicopter War had its heroes too – the 18-20-year-old cowboys of the skies, the flight crews providing protective cover, rescuing the injured, and recovering the dead.

None of the unique fighters from any war considered themselves heroes, but the statistics on what they accomplished, how warfare changed because of them, define their truths. The proudest moments in my life were serving with these men in the two years I served as a combat helicopter pilot in Vietnam.

I hope you enjoy this series. Please, pass on my subStack link josephdougan.substack.com to others who might want to know why combat helicopter pilots have been nicknamed “God’s Own Lunatics”

I Can Fly

My story begins immediately after completing flight school. Most of my class had orders for an immediate assignment to Vietnam. I was assigned to Ft. Rucker’s tactical flight training program in what they called Blackbird status waiting for my transfer to Vietnam.

While in this Limbo status, I got to fly the Huey as a newly trained pilot-in-command. I was ferrying supplies, people, etc., back and forth from the main base to our tactical training compounds around Ft. Rucker, AL. In Vietnam, this would be called an Ash-and-Trash mission.

Mostly, it was boring but allowed me to build flight time and become more familiar with the Huey. It was boring until late one February night. I was flying through a cold winter mist, and ice started forming on the windshield. I was barely trained in instrument flying; this wasn’t the time to start learning.

I descended as low as I could, looking for warmer air. It wasn’t working. I started navigating by looking out the side window, which I had lowered. The crew chief put on a harness and traversed the icy skid to clean the windshield. I couldn’t see much through the gap he made and opted to try and climb out of it.

Climbing may not make sense to you as climbing to a higher altitude will usually get you to even cooler air, but the mist can turn to pellets instead of rain. Often there is a temperature inversion due to the weather conditions where the lower air is actually cooler. For whatever reason, it worked. The windshield cleared, and we landed safely.

I learned or implemented the first rule of flying – Fly the Aircraft (FTA). It is a concept pounded into me by one of the tactics instructors, Perry C. Hopkins. At the time, he was the most decorated aviator in the US Army – he flew in Korea with the Air Force. As an Army helicopter pilot, he was shot down seven times in Vietnam. Twice, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the second highest award our country can give.

No matter how bad it seems, he stressed you have to fly it all-the-way to the ground. As importantly, knowing your emergency procedures must be second nature. One doesn’t have time to look in a book during a crisis. Emergencies must be a conditioned reflex. Prepare for the worst and hope for the best. I learned that before I read chapter one in the operators manual, I devoured chapter 7 first, the sections covering that aircraft’s Emergency Procedures. You will see how this came into play in a later chapter.

Consequently, where many consider me a pessimist, I am not. I am preparing for the worst and planning my outcome based on all available facts.

Mr. Hopkin’s guidance was foundational.

Chapter One

After a 30-day delay and a couple of weeks of leave, I left Travis AFB for Vietnam on March 23, 1968.

My arrival was delayed by a few days. Our commercial transport blew a critical hydraulic line on takeoff from Clark AFB in the Philippines. It was not a normally stocked item, so we had to wait until a replacement hydraulic line could be flown in from a San Francisco support facility.

Arriving in Saigon, I was processed at the 90th replacement center for a couple of days. I received orders to the 269th Combat Aviation Battalion in Chu Chi, about fifteen miles away. A Chinook picked me up and dropped me off at the 242nd Aviation Support Company, The Muleskinners.

I was schlepping my overstuffed duffle bag across the flight line, and a familiar face from my OCS class appeared, Doug Keith. He was not a pilot; he was assigned to the battalion as their Signal Corps communications officer.

In our brief flight line discussion, Doug told me about the various units in the battalion. If I got the choice, pick the 187th at Tay Ninh. Currently, Chu Chi was under their 28th straight day of rocket and mortar attacks. Tay Ninh never gets attacked. It was considered a Viet Cong R&R center.

I arrived at the battalion with two warrant officers returning for their second tour in Vietnam. They had an unusual story.

Both went to warrant officer flight school together. Both were assigned to the same unit in Vietnam during their first tour. Both were assigned to the same training unit as flight instructors on their return to the United States. Now, they were reassigned to the same Vietnam battalion.

Though acquainted, they would not be considered as close friends. Their assignments were coincidental. They were acquaintances, neither friend nor enemy.

We spent the first night together in a GP-Medium tent surrounded by chest-high sandbags. It was about 50 to 75 yards away from an 8” artillery emplacement. The battery was firing through most of the night. The two experienced CWO’s (Chief Warrant Officers) appeared to be sleeping through all of the outgoing explosions. I didn’t sleep much that night. My ears were not tuned to know the difference between incoming and outgoing, though I would learn soon enough.

The following morning the three of us met with the battalion commander. He said there were three openings in his battalion. There were two slots in Chu Chi with the 116th Assault Helicopter Company, The Hornets. One position was at Tay Ninh with the 187th Assault Helicopter Company, The Crusaders. He allowed us to talk it over as to who went where.

I didn’t give anyone a chance to talk. Remembering Doug’s comments from the day before, I stated that I wasn’t about to break up such an unusual assignment relationship between these two warrants, “I’ll take Tay Ninh.”

My helicopter combat career was about to begin.

187th Assault Helicopter Company

The 187th had arrived in Vietnam about a year earlier. Originally, their moniker was the Blackhawks. When an old cavalry unit was reassigned to Vietnam, the 187th’s Blackhawk name had to change. The Cav unit had been named the Blackhawks since the mid-1800’s. The 187th name was changed to the Crusaders on March 23, my reassignment date. So, I was the 1st RLO in the 187th who had never been a Blackhawk. This fact has no significance other than feeding my own humor. However, there was a particular underlying resentment between the original Blackhawks and Crusaders that still exist today. It’s ego-driven, and all helicopter pilots have huge egos.

Vietnam has two six-month weather patterns – hot and dry and hot and wet. I got there at the peak of the dry season. Tay Ninh is 22’ above sea level, and the soil is more like fine silt. As I walked across the flight line to the unit orderly room kicking up the dust, my boots were covered to the ankle with each step. In my one-piece gray baggy flight suit, I must have looked like Pig-Pen from the Peanuts cartoons.

There was no one to escort me around. Everyone was flying. I was assigned to be a section leader in the 1st platoon. Eventually, the 1st platoon leader, Russell Welch (RIP), and I met. He took me to the officer’s club to give me the general rundown of the unit and its personnel. They were short of RLO’s, and the ones they did have were due to go home soon.

Calling it the O’club may give you the wrong impression. It barely qualified as a shack. We ordered two beers from the drop-dead gorgeous, large-breasted (by Vietnamese standards – not Dolly Parton), green-eyed, Vietnamese/French Eurasian barmaid -- She opened two rusted cans of HOT Ballentine’s. The O’club had no refrigeration at the time. I took one swig and thought I was going to gag. Ballentine’s is bad enough, but hot was unbearable. Russ laughed. He said there would be times in the future when that beer would taste better than champagne. His prediction came true.

I was introduced to my section members and platoon that evening. My flying would start the next day with an initial evaluation from the SIP (senior instructor pilot,) Ed Taylor (RIP). He and I would eventually meet up again in my Dallas National Guard Chinook unit. Coincidentally, Russ Welch and I would meet up again at UNT while I was enrolled in evening Master’s classes. Russ was an attorney in Denton, TX, and taught Business Law at UNT.

Mission flying began the following day with the most experienced aircraft commanders (AC’s) in the platoon. The first day or two of flying was usually the Ash & Trash missions for newbies. This allowed the new Peter-Pilot (PP) to orient to the geography, but it was just as essential to get the platoon AC’s accurate opinions about the new pilot’s skills and what it would take to bring them up to speed. I passed.

Apparently, I was fast-tracked. Though I eventually flew with all of the unit AC’s, I spent more time with two mentors. Kirk Nivens, was somewhat of a loose cannon, but he was an incredibly skilled pilot. I learned more about low-level flying, actually nap-of-the-earth, from him than anyone.

Though I loved the adrenaline-pumping feeling of low-leveling between and below the trees, I learned more about the proper pilot techniques from Asa Vest, “If it will hover, it will fly.”

The 187th was in transition. As aircraft were retired, the replacement D-models had more powerful engines. Eventually, the unit replacements were H-models with even more powerful engines. Asa’s assigned aircraft (xx922) was the last L-9 engine, an underpowered D-model. 922’s engine only produced 825 SHP. An improved D-model had 1100 SHP and the H-model 1400 SHP. Consequently, 922 could not be manhandled like the abundant horsepower of an H-model, but it was still expected to carry the same combat number of troops! To mishandle an L-9 would cause extreme pilot difficulty. 922 had to be babied at all times. Replicating Asa’s smooth movements on the controls was imperative.

An example of what this means: Aerodynamically, a helicopter uses its most power at a hover. It is essentially generating a cushion of air below that it rides on. As one eases the controls forward to gain airspeed, the aircraft goes through a period of moving faster as it leaves the cushion behind and becomes airborne. This is known as translational lift.

If one tries to achieve this too quickly, the aircraft starts falling through the cushion and requires more power to transition to a streamlined flight. Under heavy loads in a hot climate, this lack of piloting skill often has the engine losing RPM and power, causing the aircraft to hit the ground.

Overcontrolling a helicopter is common when the adrenaline is pumping. Whizzing bullets have a way of doing that to a guy. Losing lift control requires setting the aircraft back down and reacquiring a hover to start a takeoff again. In a sweltering Vietnam afternoon where the enemy is shooting at you, this is not a desirable position to be in.

Dry rice dikes are 2-3’ high. Many pilots developed a technique where they would time their falling through (still bad technique) with the rice dike at the end of the rice patty. If the pilot’s timing was good, the aircraft skids would clip the top of the dike and bounce the helicopter up slightly, allowing the pilot more time to gain airspeed, regain RPM, and begin streamlined flying. Mis-timed, they could bounce the helicopter too hard which would spread the skids, requiring a skid replacement.

Asa was born to fly. I’ve only flown with two pilots in my life that had that innate gene. I am a mechanic of flight who could be taught. When I got into an aircraft, I strapped in. When Asa got in a helicopter, he strapped it on. The helicopter became a part of him. In all of the times I flew with Asa, we never had to abort a takeoff nor bounce one into the air.

I’ve only had two skills in my life. One was acquired, and the other is natural. I can’t saw a straight line nor hammer a nail correctly, but thanks to the AC’s in the 187th I learned the proper and often lifesaving pilot techniques. The other is my unnaturally fast reaction times and ability to think clearly under pressure. Those acquired skills and attributes allowed me to be the luckiest pilot in Vietnam.

The training was intense. The 187th was short-staffed many pilots, especially RLO’s. Ideally, RLO’s were expected to lead their platoons on flight operations. Unfortunately, not all RLO’s are competent (nor warrant officers). Russell, my original platoon leader, was transferred to the gun platoon aka The Rat Pack. His replacement was less than competent as a pilot and worse as a leader. He was my roommate. He was not disliked as a person; he was quite affable, but none of the aircraft commanders (AC’s) wanted him leading the flight.

Aviation units are structured like the rest of the military, but managing them requires more than an authoritarian style. Pilots are smarter than the average, and they are opinionated. The testing to get into military schools is a combination of quasi-IQ’s and aptitude testing. Commissioned officer schools (OCS) have one standard. Pilot training has a higher standard. More surprisingly, air traffic controllers have a higher standard than either commissioned officers or flight training. In my career, I was fortunate to lead both successfully. My Crusader platoon was not only smart, but they were also unruly and didn’t mind bucking the system. More on that later.

By mid-April, I had flown every day. Contrary to popular belief, we didn’t get shot at every time we flew. Enemy aggression seemed to come in spurts. One day someone would report receiving sporadic fire. The next day others would report activity. Then one day, all hell would break loose. That day was April 12th, Good Friday, and the unit had three KIA. A Rat Pack gunship received 6-7 hits from a 51-caliber anti-aircraft gun.

My first non-flying assignment was to inventory and prepare the effects for one of the deceased. It was a thoroughly depressing task. When deaths occur, the Army doesn’t box the personal effects and ship them to the next of kin. It is inventoried and censored. It meant that I had to review every item, look over every stored letter, picture, cassette tape, etc., to determine family suitability. I had to destroy much of my deceased’s personal belongings as being inappropriate for his next of kin. I had less than a month in-country, but death and its consequences were beginning to take on a real meaning that I had never experienced.

April ended with me sorting through the decedent’s footlockers. The time it took also meant that I wasn’t flying.

1968 Vietnam as an RLO (May68)©

Chapter Two (May) published 04/05/2022

Joseph P Dougan

Apr 5, 2022

1968 Vietnam as an RLO©

(Real Live Officer i.e., Commissioned Officer)

May was uneventful from the perspective of flying. I continued to record large chunks of flying time while building relationships with my platoon. Regardless of rank, no officer comes into a unit with a blank check of immediate acceptance and respect. It must be earned. Sometimes this happens over a period of time, sometimes never.

I am a difficult person to get to know, so earning others’ respect for me generally takes a long time. I’ve never been one to “let me be your friend” kind of leader or parent. I don’t believe I am overly strict. However, I believe in setting objectives and holding people accountable for their assignments within their capabilities. When this goal is applied to children, one must add, expect them to act their age.

Sometimes, respect can be earned by being at the right place at the right time or saying the right thing. This fortunate timing is what happened to me.

Kirk Nivens, my low-level mentor, had a penchant for flying low-level when it wasn’t necessary. (I should add that I did too, and will be covered in future chapters.) Flying low down the highway, sneaking up on an unassuming tank or APC (Armored Personnel Carrier) convoy was always fun. Tanks had 40-meter (frequency) radios which required very long vertical whip antennas mounted on the right rear. Often they would fly various flags. Flying nap-of-the-earth at 100 knots while approaching a convoy from the rear gave us the element of surprise and the ability to snap the tips off a few antennas without anyone being able to copy the helicopter tail number.

Typical target-of-opportunity

However, the large Episcopalian-looking Crusader shield painted on the nose cone gave observers a surprisingly good clue about which unit it was.

My daughter’s crochet representation of our shield … I needed something to hold the lady readers’ attention.

Our commanding officer (CO) was an old-school military authoritarian. Formerly, he was also the CO of a Warrant Officer Candidate (WOC) training company at Ft Wolters, TX. Many, if not all of my section members did not like him. After a recent low-level complaint, he put out a directive that there would be no more unnecessary low-leveling. Who determines what’s necessary? Kirk was the first to get caught. Kirk was not exactly high on the CO’s Christmas card list, so his punishment would make a prime example. The CO wanted a Court Marshall for violating a direct order.

After hearing the CO’s decision, the platoon ACs (aircraft commanders) were going to mutiny, literally. After talking to the group of ACs, they agreed to see the CO in his quarters to express their disagreement with his punishment.

Each side had backed itself into an unwinnable corner. We Quit if there is a Court Marshall. I proffered a potential solution.

Kirk was in my squad and a short-timer; I would take full responsibility for any further infringements from his behavior. If he violated any more rules prior to his departure, the CO could issue two Article 15’s, one to me for failure to supervise. An Article 15 is not a Court Marshall. It is non-judicial punishment, but fines and loss of rank can be imposed. My recommendation ameliorated the discourse.

The CO, ACs, and Kirk accepted my plan. My offer was not pre-planned or done out of bravado. To me, this was the most acceptable solution. Regardless, it had a lasting effect. Kirk went home with a clean record, and I earned newfound respect from the platoon, a unit I would eventually take over as their platoon leader.

Why a VC R&R Center

Our compound had been void of enemy activity due to a humanitarian event the previous year. An important Vietnamese prelate, who was reported to be a Cao Dai priest, was dying from some ailment. A US physician stationed at Tay Ninh saved the head muckity-muck priest’s life.

Cao Dai is a major Vietnamese religion and represented about a third of the population. Cao Dai is an amalgam of Buddhism, Christianity, and whatever feels good. Regardless, Tay Ninh is the center of their activity. Tay Ninh’s ornate Cao Dai Temple is the Vatican for their religion. After the priest was cured, he promised a year of peace. A year and a day later, peace ended, and our real war began.

Towards the end of May, Tay Ninh lost its reputation as a VC R&R center. On May 20th, there was a full-scale rocket and mortar attack followed by a breach in our firebase perimeter. Captain Ron Cody, Rat Pack platoon leader, took to the air to stop the onslaught. In his quest to get into the air as quickly as possible, he didn’t have time to dress appropriately and took off in flip-flop sandals and an old zip-up flight suit. As green AK-47 tracers could be seen overhead and down the flight line, Ron made single-ship gun runs down the breached section of the perimeter using his mini-guns.

The VC breach was successful; they got inside our perimeter, but their objective was not achieved. Artillery guns were lowered to the horizontal, and beehive rounds – glorified shotgun shells the size of an eight-inch diameter artillery round -- terminated the onslaught. One shell could destroy virtually anything the width and depth of a football field.

This attack forever changed our days in Tay Ninh. By the end of my Vietnam tour, other aviation units were sent nightly to help with our firebase defense. They jokingly tacked up signs around our compound nicknaming us as “Impact Area West.” This was a reference to signs seen on the roads traversing US military bases. These are No-Go areas where artillery or bullets would be impacted during training.

One Lucky Dude

Towards the end of my sixth-week in-country, I was flying as a Peter-P with Eric Mercer in his aircraft “Old Magnet Ass.” Whether it was Eric or the ship, the moniker was accurate. OMA attracted bullets.

We were flying as the second flight of ten helicopters with our sister company, the 116th Assault Helicopter Company. The LZ was in the pineapple fields southwest of Saigon. The Pineapples were a notoriously hot (enemy activity) area of operation. Because the Hornets had inserted troops immediately before us, our gunners were not allowed to fire their weapons on short final or takeoff. They might inadvertently shoot a friendly troop. It was the Crusader’s first lift-in, which usually means that the aircraft commander is flying, which Eric was.

Routinely, most helicopter troop insertions would drop off 60-70 grunts, about half an infantry company. The flight would return to pick up the remaining company to reinforce on the second insertion. If it were a typical bad day at Black Rock, the enemy would allow the first flight in before opening fire. The VC knew we would have to reinforce or return to extract (retreat) the infantry under siege. Either way, the VC/NVA were going to shoot up a bunch of helicopters.

We were prepared for a hot LZ, so two companies were being used on the first insertion/s instead of the routine round-robin for support. The second flight would be on a short final as the first flight was departing. The infantry knew they would need a maximum number of soldiers on the ground as soon as possible to gain an advantage.

When we landed, I observed the tracers whizzing through the LZ. Tracers are phosphorous-illuminated bullets used to guide the machine gunner’s aim. They are the fifth round of the gunner’s linked ammunition. When you witness a stream from a machine gun, know that there are four real bullets between each light trace.

Eric sat calmly at the controls waiting for the helicopter in front of us to drop their troops and take off. I turned to look out the left cargo door when a pineapple plant rose out of a spider hole on the berm about 20 yards away. Our gunner that day was a former infantry machine gunner. Without asking permission, though it was a no-fire area, he squeezed his butterfly trigger while the machine gun was still pointing at the ground. He walked the rounds up and into the human pineapple plant. The enemy got off a quick burst of AK-47 before he started dancing around. His movements looked like the assassination scene of Bonnie and Clyde. We felt the VC’s bullets hit the aircraft, but we didn’t know where or how badly we were damaged. Now was not the time to get out and look around.

Eric took off and returned to a safe area to check for damage. We found that one of the rounds took a large chunk from the yoke behind the large bolt that attached the rotor blade.

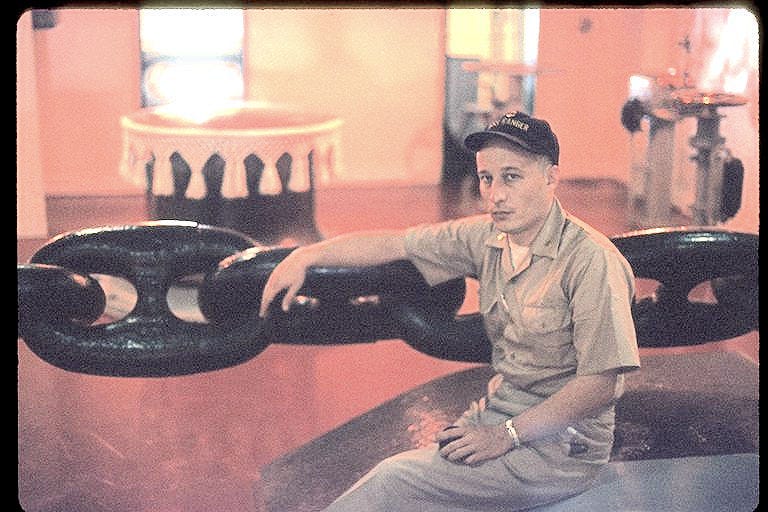

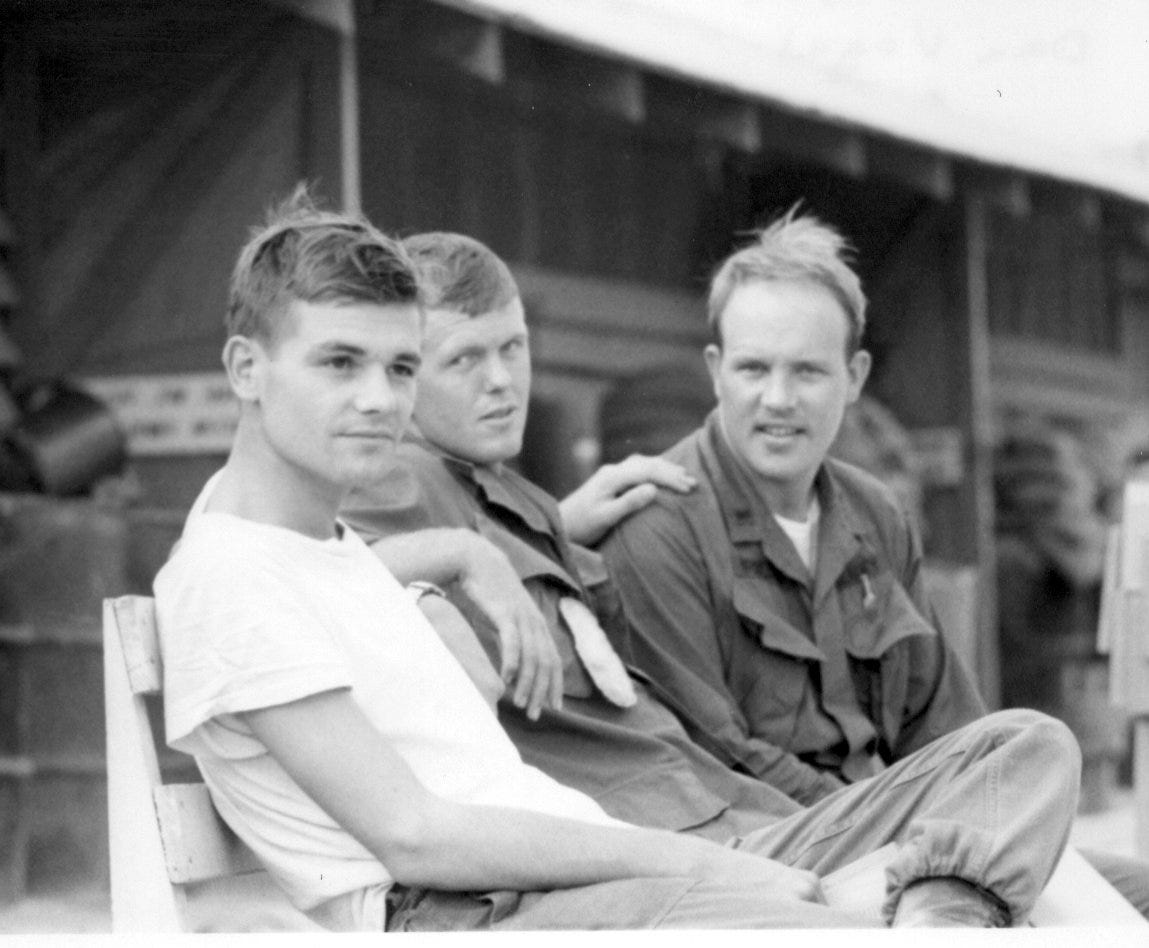

My crew chief, Scotty, working on the rotor head (yoke)

As stated, that was my sixth-week in-country. It was also the last time that any helicopter I flew in Vietnam [through two different tours] received any combat-induced damage.

Fear:

Honestly, I cannot think of a time when I was worried about combat. I never thought about it. However, one of my worst frights happened late one night while I was still a PP (Peter-Pilot.)

Each evening one aviation unit in the brigade area is on call to handle emergency calls (Tac-E’s … Tactical Emergency). Simply put, being called out on a Tac-E means that your life, crew, and helicopter are expendable, if necessary, for the sake of others. Most missions are one or two-ship medevac or ammunition resupply missions. Occasionally, an entire aviation company is called out.

A second company assigned as Tac-E standby is assigned as a backup but was seldom used. Most second-company standby pilots and crews go to their clubs, supposedly doing everything in moderation, etc..

A third company is a designated reserve unit with no restrictions on its activities.

One night, while on third standby, everyone was drinking and carousing in their clubs, which included drinking to excess, a common activity for all flight crews. Internal company communications with the operations center were done on field phones to each of the clubs. The phones were seldom used.

One night around eleven, the distinctive chortle-ring from the TA-312 hand-cranked field phone went off in the O’club. The din in the club immediately went silent. No one calls that phone, especially at 11:00 PM. This call could not be good news.

Not only was this a Tac-E call-out, but it was also for our entire company. A firebase was under siege and possibly being overrun. Launch immediately.

There was hardly a sober pilot in the unit. I was flying with my new platoon leader. He was stone-cold sober due to his religious beliefs. The problem was, he was one pilot that couldn’t think or fly, at least not simultaneously. Now that’s scary, daylight or dark.

Flight crews staggered to the flight line and somehow took off without incident. Night formation flight is hazardous enough sober. Tonight’s flight would add enormously to our pucker factors. To add further tension to the event, enemy activity was peaking. For safety, the flight was ordered to turn off our navigation position lights and refrain from using our landing lights on the final approach. In daylight, we flew approximately two rotor disks apart, approximately one hundred feet. This night, all bets were off.

Formation flight in helicopters is generally reported as any two or more helicopters flying at the same altitude, in the same general direction, in the same general vicinity, and going to the same objective. Fortunately, it was a clear night. Tonight, however, it was ten helicopters staggering in the same general direction, sometimes at the same altitude (as we were flying through it.) Our formation could be seen from horizon to horizon. The lead helicopter could have been in Da Nang and the trailing helicopter in Saigon. Until …

On the final approach, flight sobriety was immediate as the green and orange tracers started whizzing by. The flight tightened up to one rotor disk, and we were in and out without incident.

Still, it was the scariest night I had in Vietnam, and they were shooting at us too!

Aircraft Commander:

Becoming an aircraft commander requires orders from the Company Commander, but they are not issued until the existing platoon aircraft commanders vote for approval on the individual. Our unit usually set the minimum combat time for consideration at three hundred hours of in-country flying (total time over 500 hrs.) I don’t know if they were that desperate for RLO’s in a leadership position, but I made aircraft commander at 185 hours. I like to think it was because I was that good, and they were not that desperate.

Some personnel issues had to be resolved before officially taking over as 1st platoon leader. The existing platoon leader was transferred to battalion headquarters. The individual was an extremely nice guy but was a below-average pilot with minimal flying skills or cognition to lead a flight of ten helicopters.

Another issue was the other platoon section leader and my roommate, Dan Vogle. He outranked me by 24 hours. By his date of rank, he would be the designated 1st platoon replacement. The solution was to transfer Dan to the gun platoon as an assistant platoon leader, where he wanted to be.

I inherited a platoon with no RLO section leaders but was heavily staffed with two unique assets. The experience, competence, maturity, and leadership of the existing AC’s were exceptional. The second and more critical asset to the future was an overabundance of upcoming ACs with above-average flying skills from my flight school class. Most of them already knew me and what to expect; those that didn’t know me received immediate G-2 (Intelligence report,) which cut down my leadership transition time.

I was now twenty-one leading a group of 18-19-year-old kids in combat and making old men out of them before they turned twenty. Before I left the unit, this intrepid group of men and those from the other platoons would go on to distinguish themselves as true aviation heroes.

Each war has its standouts who made significant changes in warfare. WWI had the Red Baron dueling the pilots flying their bi-winged Sopwith Camels, and aviation warfare began. WWII had Spitfire pilots defending Great Britain. Airplanes made control of the sky imperative to protect those on the ground; boots-on-the-ground still would determine the fight's outcome. But in Vietnam, it was the helicopter … more specifically, the Huey, its air mobility to mass the troops, and the fearless flight crews. Survival rates for the injured warriors over previous wars skyrocketed as intrepid flight crews risked it all, ensuring no one was left behind. However, the casualty rates for helicopter flight crews were some of the highest recorded of the war.

In June, I would begin leading my “Band of Winged-Brothers.”

1968 Vietnam as an RLO© (June 1968)

Posted 04/19/2022

1968 Vietnam as an RLO©

Joseph P Dougan

(Real Live Officer i.e., Commissioned Officer)

Chapter Three (June)

Management Philosophy

I am not sure where I learned my style of management. I have never been an authoritarian ruler. But, I find being strict in what I expect is preferable. Strict might not be the best choice of words. What I mean is, I prefer to tell you exactly what I expect, not how to do it. I have often said, I am not a perfectionist – I just require it of you. I will look you in the eye and call you out if necessary. However, I will listen to your solution and make appropriate decisions. You will have the opportunity to change my mind. If your way does not clearly present a better outcome, we are doing it my way.

Due to their nature, teenage combat helicopter pilots have an independent streak that often is in contravention with the “book” or often common sense. It is the latter that always causes them the most problems.

June was a sweltering and dry month, and we had been flying excessive amounts of hours. By 1st Aviation Brigade orders, pilots were on a 140-hour-per-month restriction. If a pilot exceeded 140 hours in a thirty consecutive day flying period, they were not allowed to fly without flight surgeon approval.

We were always short-handed, and the flight surgeon kept a stack of medical release forms available. Walking without falling asleep and chewing gum simultaneously was about the only medical requirement for proof of stability. Most warrant officer pilots did not complain about excess flying hours; flying was what we all wanted to do. I had additional leadership duties to keep me on the ground; I wanted to fly too. Our thirty-day flying record was posted on our platoon flight assignment board.

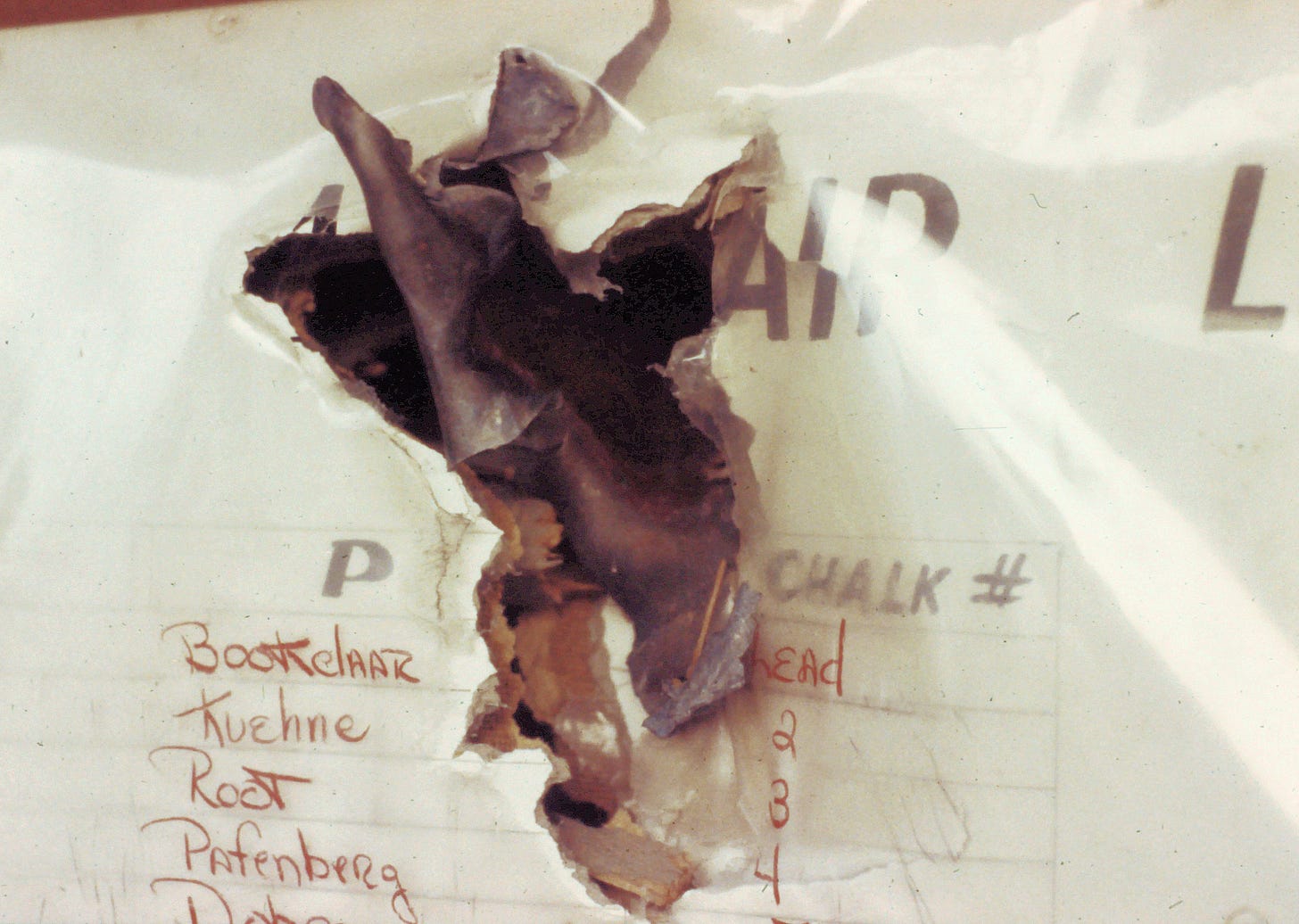

Daily Assignment Board and accumulated flight times.

At one time, I was a low man in the platoon with 170 +/- hours. I’ve seen some pilots in our unit with over 210 hours in thirty days. Any time off for a flight crew was appreciated, but teenagers flying a half-million-dollar helicopter was more fun than a ride at Six Flags. No one wanted to stay down.

Excess flying was tiring enough for the pilots, but the crew chiefs and gunners not only flew all day with us but had to perform helicopter maintenance when we were not flying. They were the unsung heroes. Every twenty-five hours of flight time required a couple of man-hours for routine maintenance. This was often completed in the dark by flashlight. Every one hundred flight hours requires extensive maintenance in the maintenance tents using multiple mechanics and technical inspections.

What To Do When Not Flying

(Hint: Don’t piss off the boss)

One day the infantry unit we were working with uncovered a large cache of enemy supplies buried in an extensive tunnel complex. Extracting, inventorying, or destroying the cache would take most of the day. In these extended-stay situations, the infantry battalion commander would release the Crusaders. The 187th would be reassigned to fly for another unit. This battalion commander knew how much we had been flying. Rather than releasing us for additional flying, the colonel told us to land at Chu-Chi; wait to be called out, which was not expected. He effectively gave us a maintenance stand-down day and a chance to relax. It was going to be a late morning and early afternoon basking in the sun by ten helicopters lined up tail rotor to rotor.

However, there was maintenance to be completed by the downed crews before any resting. Frankly, most pilots are worthless for helicopter maintenance, and I lead the pack. There are still areas where the pilots can help the flight crews, no matter how insignificant. It might mean using rubbing compound to take the scratches out of the plexiglass, dusting the floors, or tossing the crew chief a quart of oil — everyone pitches in on stand-downs.

After trying to do my part on my helicopter, I walked down the flight line to check on everyone [also, technically, my job.] When I got to one helicopter, I saw the crew chief balancing on the tail stinger to service the tail rotor gearbox. The gunner was on top working around the rotor head. Two pilots were dead-asleep on the cargo floor.

I was immediately furious; this is not the example for officers to set. I woke both pilots and had them meet me about fifty yards away from the line of parked helicopters undergoing maintenance. I allowed the pilots to explain their justification for sleeping while everyone else on every other helicopter was working … i.e., enough rope to hang with. They had no acceptable excuse.

In language that I knew they would understand, I explained what I expected: If you see me working, you work. If you see me going to a hot LZ, you had better be tucked in closely behind me. And, if you see me fxxxing off, then go fxxk-off. But, until that time, you’d better be doing something to contribute, or I will be working on your transfer to a Cav unit.

At the time, flying for the Air Calvary was not a desirable flying mission. Oh! The CAV gets to wear those cute cowboy hats and ascots, but no one volunteers to join a Cavalry aviation unit unless they have a death wish.

The errant pilots got the word, and more importantly, those words made the rounds.

RHIP (Rank Has Its Privilege)

I tried not to abuse that idiom, but sometimes ya just gotta. 😊

My roommate, the 1st platoon leader, was transferred to our battalion headquarters in Chu Chi. I was promoted to be the 1st platoon leader. One of my men and flight school friends, Ron Timberlake (RIP), redesignated me and presented me with my new nickname, a cap with “ ‘Toon Daddy” embroidered on the back. It was a good great feeling to have that acceptance early on.

Coincidentally, the 187th received notifications that we would soon receive the first three shiny and new H-model Hueys, which began our helicopter upgrades to a more powerful machine. One Huey was assigned to the Company Commander for his C&C (Command & Control) ship. The other two went to the 1st and 2nd platoons. There was no reason to listen to my senior aircraft commanders argue over who should have it. I surely didn’t want to play favorites, so I took it! 😊

UH-1H 67-17558, assigned to the 1st platoon, would need a crew chief, and I designated a young SP-4 whom I had been flying with regularly, Doug Scott aka Scotty. [originally published as Herman Scott another 187th member]

Specialist 4th class is a rank just above a PFC (Private First Class). A crew chief is normally an SP-5. Scotty had not held the SP-4 rank for very long and was technically not due for promotion.

I checked with his platoon sergeant, and he agreed that Scotty was going to be one of the better crew chiefs, so I put in my request with our CO, which he approved.

Crew Chiefs normally name their helicopter and have the company artist decorate the doors e.g., Old Magnet Ass, Flying Frenchman, The Rebel. Once again, I broke tradition. I named 558 as The S💧 A💧 D💧 Mrs💧 The initials are my wife’s, and each period was a painted teardrop. Admit it! … it was original and cool.

Scotty on 67-17558

This usurping of tradition may not have been Scotty’s preference, but I made it up to him, though not without my satirical (sadistic?) humor at his expense.

One day, after receiving Scotty’s promotion orders, I spent excessive time complaining about any nit-picking thing I could find wrong with Scotty’s aircraft. I told him to come to my room after his post-flight maintenance, so we could “talk about” his performance.

Facts escape me over time, but I believe our platoon sergeant was there too. When Scotty came in, I gave him a faux dressing down. I pushed my attempt at humor too far. Most people don’t understand my humor, and the following is a classic example of why. Sometimes, I just ain’t funny.

Using trumped-up charges, I complained that the platoon leader deserved a responsible SP-5 as his crew chief when our new aircraft arrived. I did not need an inexperienced SP-4, especially one who couldn’t pin his rank on his collar correctly. And, I removed his SP-4 pin from his collar. Scotty was crestfallen. I’d overstepped my bounds.

However, though clearly nonplussed, his recovery was quick when I showed him the SP-5 pins pulled from my pocket and pinned them on. We promoted him months ahead of schedule.

There is a certain irony in all of this, and it has haunted me ever since.

This psychological faux pax was in mid-June. Scotty flew as my crew chief on 558 from June to October. He also flew occasionally as my crew chief on SMOKEY when I transferred to the gun platoon. I’d estimate we have 600 or more hours in the air together.

I tried to meet up with him a few years ago. He is a professional engineer in Atlanta. He doesn’t remember me from Adam…. ☹

PTSD is a strange bedfellow.

Since he doesn’t remember me, do I still owe him an apology?

Next month’s chapter, July, starts off with a bang. And I started getting in FNG’s (Fxxxing New Guy’s) RLO’s to train. What was your first day flying like? My new section leader, Jim Ray, has a story to tell.

1968 Vietnam as an RLO© (July 1968)

Published May 4, 2022

Joseph P Dougan

1968 Vietnam as an RLO©

(Real Live Officer i.e., Commissioned Officer)

Sometimes, not everything we wrote home was true. And sometimes those enemy rounds were getting a little too personal.

Chapter Four (July)

Happy Anniversary!

July started off with a “bang” in more ways than one. I was starting to get the hang of being a flight leader after being made an aircraft commander and had accumulated a large amount of combat time for my brief time in-country. Our week-long R&R’s were normally taken during the last six months of one’s tour of duty. Australia, Hong Cong, and Thailand were popular destinations, especially if you were not married. Hawaii was generally reserved for married men to meet up with their wives.

Though I’d only been in Vietnam since late March, I requested to take my R&R early. July 1st would be our first wedding anniversary. The CO granted permission, and I was scheduled to arrive in Hawaii July 2nd – a day late, but close enough. Sheila planned to get there a day earlier to prepare for my arrival.

My scheduling was based on the Vietnam time zone. I had forgotten to consider the international dateline. I arrived on July 1st. Needless to say, Sheila was not at the airport to greet me. I went to our hotel and saw that she had checked in a little earlier. Another surprise was in order.

I stopped at the hotel florist and picked up a dozen roses. Then I grabbed a bellman to knock on the door to announce that he had a delivery. The rest is history. Yes, she was surprised.

We were staying at the Hilton Hawaiian Village. If you’ve ever watched the old TV series Hawaii 5.0, HHV is that large, pink-tinted building in their opening credit scene. Our room faced the main street; ocean views were out of the limited budget range of a 1st Lieutenant. Both of us were exhausted from our long trips. Mine took about eighteen hours with refueling stops. Her trip was not as long but emotionally straining -- more on that in another chapter.

Around 1:00 AM, both of us were sound asleep until an ambulance blaring his siren went barreling down the street. Sirens at Tay Ninh were used as our advanced notifications that incoming rockets or mortars were detected inbound. Conditioned reflexes took over as I rolled out of bed to get on the floor. It was then that she realized that all those “things are hunky-dory” in my Vietnam letters were not based on facts.

Still, the trip was memorable once we got over the emotional hurdles. Ron Hopkins, a senior 1st platoon member was also on the same R&R. Though single, he was allowed to take his R&R in Hawaii because he was from Honolulu.

He guided us through our visit, avoiding the typical tourist traps. Sure, we went to the Kodak hula show, but that was because Ronnie had a friend who was one of the dancers – and she was not the big’un who looked like she kept a whole ranch of silkworms working overtime for her dresses.

After I returned to the 187th, I met a new roommate, Jim Ray. He was assigned to my platoon to fill an open section-leader position. He was only my roommate for a short time. I think I moved him to another room in a desperate attempt to get some sleep. Jim was and is the funniest person I’ve ever met. He would keep me up to all hours reciting stories that were so funny I’d be crying (laughing) myself to sleep. He’s been a lifetime friend and is a natural entertainer.

When I asked Jim where he was from, he said Arkadelphia, Arkansas.

“Arkadelphia? Where is Arkadelphia?”

He said, if you haven’t heard of Arkadelphia, then I know you’ve never heard of Gurdon, which is where I am really from.

Good Morning Vietnam

Jim’s introduction to Tay Ninh was literally a baptism by fire. He had not taken his in-country check ride, but the infamous Col. Patton’s (General Patton’s son) mechanized infantry unit was under attack and needed emergency CS gas-ship support. CS is a highly potent non-toxic form of tear gas. The 187th AHC was already on missions elsewhere.

WO John Wilson had recently been promoted to AC and needed a “ballast-body” (sandbag) to hold down the co-pilot’s seat. Center of gravity limitations normally required two people in the front seats. With all of the available pilots gone, John told Jim, whom he had not officially met, to grab someone’s helmet and start a pre-flight inspection while John received the situation briefing from our Operation Officer.

Jim has recited his first day of flight story at every reunion and gathering for the past 50-plus years, and his version gets funnier every time. I can’t do it the humorous justice it deserves, but I can at least cover what happened to the two best friends I’ve had for over 50 years. This story didn’t involve me, but it is too good not to pass on. It was on my watch.

John, being new as an AC meant he had even less experience dropping CS gas. Though gas drops are not an uncommon mission, it was not routine, especially for a new aircraft commander. Jim was an infantry 1st Lieutenant straight out of flight school. Due to their close-in support requirement, dropping CS gas can be extremely dangerous. The drop missions were usually low to prevent accidental drops onto friendly troops.

The flight crew ejects the large gas canisters one at a time. An adjustable timing mechanism on each device detonates them a safe distance from the helicopter, exploding a cloud of CS gas over a large area. Often, the Peter-P will wear a gas mask in case of a gas leak, or they fly through their own cloud of CS. Gas mask lenses are not prescription ground optics and distort visual perception, so most AC’s prefer to cry a lot when flying. 😊

Weather variables dictate the flight path, so the gas cloud is not blown back onto the friendly troops. This often means flying directly over enemy positions. Consequently, the enemy will not be too happy about what is happening.

Any flying altitude higher than 1500’ normally is safe from small arms or rifle fire. However, these CS drops would be at 1000’ or below to ensure accuracy. One of the first drops John made was much lower than 1000’. This level is considered to be a dead-man zone. John’s drop was so low that an enemy RPG (Rocket-Propelled Grenade) was fired at them. It went through Jim’s windshield across the cockpit striking John in his ballistic helmet and exited out the green-house window above his head.

It struck John with enough force that it dislodged John’s pilot seat from the breakaway latch and left him strapped into his seat but lying horizontally on the rear cargo floor. His crew pushed him back into a flying position.

Most RPG’s don’t explode instantaneously. The delay at impact allows the rocket time to penetrate deeper into an earth bunker before the blast, which maximizes damage. At the speed the RPG travels, this detonation delay through a helicopter’s windows equates to distance. These few milliseconds were enough of a delay that the rocket detonated after it had exited through the helicopter's roof and blew above the rotor head.

Jim, obviously flying at this point, looked over at John to see Plexiglas stuck in his face and bleeding from a large hole in the side of his nose. John’s only comment was to fly faster to get back to Tay Ninh. Jim was only flying between 30-40 knots. The helicopter couldn’t go any faster without inducing a severe vibration.

They made it back safely and in post-flight inspection saw significant amounts of damage to the blades and rotor head. The helicopter should have self-destructed in the air. Had the rocket struck metal instead of the plexiglass windows, it would have. Divine Intervention saved the day, again.

John left the flight line and started towards the dispensary to get his wounds treated; Jim headed to the barracks.

Huh? John said, NO!

Go pre-flight another aircraft and get the CS gas transferred.

“You mean we are going back out?”

“W e l c o m e T o T h e 1 8 7th C R U S A D E R S!”

By the time John was treated and Jim got the canisters transferred, Jim’s infantry training kicked in.

“You know these fuses can be set with a longer time, so we don’t have to fly so low?”

The delaying fuse adjustments were made.

I am sure that this is the day that Jim made the commitment to set his sights on the Rat Pack gun platoon. He preferred being able to exact revenge. Eventually, he became the Rat Pack platoon leader.

It was not just summer, but in August, things started really started heating up

1968 Vietnam as an RLO© (August 1968)

Published May 20, 2022

1968 Vietnam as an RLO©

Joseph P Dougan

(Real Live Officer i.e., Commissioned Officer)

Chapter Five (August)

As stated in a previous chapter, these stories are from my perspective as I experienced Vietnam. Others who participated in my reported events have differing views. We each saw things in a different way. Sometimes our brains only recreate the way we thought or wanted it to be, but it is always nice when there is verification for what we do remember.

One pilot took objection to my original story as published last year on my FaceBook site. In today’s update to that story, I have a rare treat and vindication. The last known survivor, Captain Harold Greer was the co-pilot in the following story. It was a transmission failure in helicopter 65-12869. I tracked Harold down to get his viewpoint on my narrative. His statement is included in the appendix at the end of my August chapter.

Always Trust the Instruments

August turned out to be another noteworthy month illustrating the stresses of combat.

One hot afternoon, our C&C (Command and Control) ship was being flown by our company commander Major Russell Folta (RIP). It was a trying day with the flight of ten orbiting excessively while everyone “upstairs” seemed to be oblivious.

The company flight lead was CWO Joe Gorecki, a hard-core, matter-of-fact, enlisted Marine prior to attending warrant officer flight school. In our battalion SOP, regardless of rank, the flight lead directed the platoon operations during missions for both slick platoons. Often this was an experienced warrant officer because there were few qualified commissioned officers in the 187th AHC at that time. Joe not only was a good pilot, but his previous Marine training made him a natural flight leader.

Joe Goreki

The caterwauling on the platoon radios was becoming more pronounced due to the day-long constant delays and persistent orbiting. Joe was a man of little patience, and his frustrations were starting to show. Abruptly, Major Folta made an announcement. His transmission oil pressure gauge was starting to fluctuate.

Transmission gauges are the few items on a helicopter never ignored. You can lose a tail rotor control or an engine and still land safely. A helicopter cannot fly if the transmission and rotor blades are not turning.

In my research for this story, other platoon pilots reported that this aircraft had transmission fluctuation issues for weeks.

Unfortunately, every maintenance re-inspection had revealed nothing. Still, one NEVER ignores the transmission for any reason. Get the helicopter on the ground, and get it on the ground, NOW!

The flight had been working on an extremely long flying day. We still had troops on board for one final insertion, but we were all starting to run low on fuel. Pressed to complete the mission, Major Folta elected to “fly it and watch it.” This statement is a term that maintenance uses in our logbooks to respond to our maintenance write-ups when they could not find a cause for the problem reported.

Once Major Folta made his commitment to keep flying, the caterwauling became instant radio silence. One could almost hear every pilot in the flight gasp in disbelief. Every pilot and crew turned their eyes skyward.

C&C always flew around 2500’ to 3000’. Within minutes, Major Folta declared an emergency. His transmission was seizing. Everyone in the flight watched him nose his helicopter over to the race for the ground. It was for naught. We watched as his rotor slowed while the transmission was seizing. Major Folta’s helicopter then went 90 degrees vertical -- nose down. The last anyone saw, the blades were barely turning. One could almost count the blade RPM. The fuselage rotated approximately three revolutions around its axis during the free fall.

All watched the crash as it impacted a partially filled rice patty. No one could survive that crash. The splash was epic and shot water and mud 75’ into the air. Flight Lead said we needed to drop off the troops and refuel before coming back and securing the crash site.

I objected. I requested permission to go look but was denied. Joe said, “Stay with the flight.”

I was the ranking officer in the flight, but the flight lead was still technically in charge. I overrode his decision without getting into an argument and declared I was taking charge of the flight. Though it wasn’t part of my decision process at the time, whether Private or Captain, “the next man up” has been a constant in US warfare training. My decision to take charge, due to rank, was also stated in our battalion SOP. It was the right thing to do. I broke off the last three aircraft in the formation to inspect the crash site. Joe, to his credit and training, made no more objections.

There was no logical explanation for what I found when I arrived at the crash site other than Divine Intervention. Sometimes, the “Jesus Nut” (one large nut that affixes the helicopter's rotor) has a significant meaning. The crashed helicopter was sitting perfectly upright on its skids. There was smoke coming out of the engine compartment, and their crew chief was using the fire extinguisher to quell the flames.

Remember, the last anyone saw, C&C was vertical and rotating on its axis.

Fire extinguishers in hand, my three flight crews went to assist in extinguishing the engine fire. I had the onboard troops deploy for security. The flight was recalled to bring in reinforcements. Virtually everyone on board the C&C was ambulatory.

I can remember watching the three flight crews moving across the rice paddy to help. And, I remember seeing the infantry deploying to set up the protective perimeter. I don’t remember if the 187th or Medivacs evacuated the injured. Due to the obvious back injuries, I would assume Medivacs. I remember nothing about the rest of the day, how we got home, or anything else that happened that evening. It is as if that time didn’t exist. To watch the horrific event was disturbing at any level. With time to reflect the unexplainable takes over the brain wondering how was it possible for nine people to survive what appeared to be a half a mile free fall.

Every person on that helicopter lived. Most had compressed spinal injuries. This is significant. If there was any forward motion when a helicopter crashes, it would cause whiplash injuries. At that height and impact speed, all would have had severed spines. They had to have landed perfectly vertical only to have compressed spines. Regardless, there is no conceivable explanation for what happened, which a flight of ten helicopter crews witnessed.

At the end of this chapter, I have included the actual Army accident investigation report, which indicates there was some rotor RPM left to break the fall. Though from what the flight saw, you’d have a hard time convincing anyone there was any significant rotation in the blades. Divine Intervention.

I met Major Folta at our unit reunion in 1998. He told me no one on his crew remembers anything other than the initial gauge fluctuation. Neither of the crew members has been found.

Major Folta wrote a letter to me after our reunion. He was thankful to hear “The Rest of the Story” and my intervention but still considered the event a “hard landing.”

No! Shit! Sherlock!

Here’s Your Sign

At the end of September, the gunner from that crash tried flying again. It was payday, and most everyone got paid in cash. While flying to and fro on a hot afternoon, he had turned 90 degrees to put his feet up on the side seat to catch a nap between troop insertions. I got a call from an aircraft behind me wanting to know what I was streaming out my right door.

I turned and looked to see my sleeping crew member. His right pant pocket was flapping in the rotor-disturbed air. Every time his uniform flapped, another bill peeled off the payroll wad he had stuffed in his pocket. I think that was the last time he ever flew.

August Psy-warfare:

As I explained in an earlier chapter, rocket and mortar attacks on Tay Ninh started in May. This concluded a year-long moratorium of violence against Tay Ninh. It was a courtesy. Our medical doctors saved the life of a failing Cao Dai priest.

The frequency of rocket and mortar attacks became so common that visiting units started tacking up signs “Impact Area West” by the time I left Vietnam. Impact Area West are signs used on the roads surrounding the landing (impacting) areas for artillery, bullets, or high explosives on military training bases.

Though not a daily occurrence, rocket and mortar shelling became commonplace. Unless one heard the high-pitched squeal of the incoming rockets or verified that the thuds from impacting rounds were close, one often didn’t get out of bed to go to a bunker. Some slept through the attacks, too tired to be aware.

Tay Ninh base was a very large compound housing artillery, engineering, and aviation units. Hearing impacting rockets on the far side of the compound seldom got anyone’s attention. One would listen to see if they would be “walking” the rounds to our area. If not, go on about what you were doing.

Tay Ninh base camp today facing north, twelve miles from the Cambodian border. It is approximately one mile in diameter. The green strip left of the runway was where we parked our helicopters. The new orange top buildings in the west lower center was our company compound.

By August, all of the barracks had been surrounded with 55-gallon drums of dirt or sandbags to absorb shrapnel. Many of us had folded our bed frames and slept a few inches off the ground. The bed level was below the protective barrels. Unless your hootch took a direct hit, you would be ok.

Officers filled the protective drums after the moratorium ceased.

[In case you couldn’t tell, I took all of the pictures, so I didn’t have to get dirty … I am much too delicate for manual labor] 😊

The officer’s area took three direct hits while I was there. The first rocket impacted a few yards in front of the second platoon barracks and directly in front of the officer’s shower. The concussion destroyed the shower. Shrapnel went through the front wall and out the backside of the barracks.

Officer’s Shower ... or what was left of it

This was the only rocket landing in the officer’s area that imposed serious injuries. With no shrapnel barriers at the time, two of the officers were medivac’d to Japan. One pilot had been sleeping on the top bunk bed. No one slept on a top bunk after that.

A few months later, the officer’s shower took another direct hit. Sometimes the gasoline-fueled immersion water heater at the top of the shower’s water tower would expose flame from its chimney if the gas was flowing too freely. The exposed fire made a perfect aiming point for enemy rocket and mortar adjustments.

August brought on a different style of psychological warfare. Instead of random attacks, the Viet Cong start dropping in a few rockets a day and usually at the top of the hour. This went on for a couple of weeks before it ceased. The timing psychology had its effect, however.

It got to the point that one would look at their watch near the top of the hour. We’d stroll by the nearest bunker to listen for the squeal of rockets or woosh of mortars. The louder the rockets got, the quicker the decision to enter a bunker or not. The thuds would determine which section of Tay Ninh was being shelled. The first few days of attacks were often laughed off. After a week or two, these attacks started to take their mental toll.

The shelling finally stopped. But, not knowing what time it was didn’t. Most were subconsciously twitchy at the top of the hour.

Flying with the 187th generally started with an early morning breakfast or nothing at all. My breakfast normally consisted of two Dr Peppers on the way to the flight line. Lunch was generally cold C-rations. Supper could be nothing, liquor or beer at the officer’s club, or cooled leftovers from the mess hall.

One day we got lucky early. After their first insertion, the infantry battalion uncovered a significant tunnel complex and supply cache. As illustrated before from a previous story, the battalion commander did not have us reassigned to another unit. He kept us on standby, giving us an unscheduled maintenance stand-down day at Tay Ninh.

This early morning gift allowed the CO to call the mess sergeant to prepare a hot lunch for everyone. The cooks fixed a feast of fried chicken, mashed potatoes, gravy, and yellow corn. Except for Thanksgiving or Christmas, the unit seldom got to eat a hot lunch at our mess hall.

…………….

Clarification … You need to understand the following narrative for the rest of my story to make sense.

To help analyze jet engine performance, Air Force tower operators are trained to describe the exhaust flames from accelerating jets. I don’t know how true that is. I think it is another Air Force joke to allow jet jockeys to cowboy around the countryside and make helicopter pilots jealous.

Occasionally, the passing jet jokers would ask permission to “boom” the tower. This was a jet jockey Six Flags Over Saigon thrill ride which was not allowed at Tân Son Nhât AFB in Saigon. I think the noise scared the MACV colonels and general teeing off at the TSN golf course. YES, there was one!

The fighter jet would rapidly descend and roar down the runway completing a low pass. After the Zoomies passed the tower, the JJ’s would kick in their afterburners, shooting out a huge flame as they rocketed towards the sky. As they turn skyward, the explosion of their afterburner rocks the ground reverberating off the runway -- Totally Impressive … Awesome.

………………………………………………..

INCOMING!

Everyone sat down to their fried chicken dinner, and the conversations and laughter became louder and more animated. Then, at almost the same time, everyone went coldly silent as each started to pick up the faint incoming rocket-sounding whines. It sounded like the beginning of a significant rocket attack. The shrieks became exceptionally loud -- louder than any conventional rocket attacks we had experienced. Frankly, it was frightening. Louder and L O U D E R! – it sounded like we were taking a direct hit on the mess hall.

WHOOM! WHOOM!

When that explosive concussion hit the mess hall, tables and chairs went flying. Everyone in the room dove for the floor as dust and dirt fell from the ceiling and windows. There was chicken, mashed potatoes, and gravy spread everywhere. I can remember looking across the room at our company commander. He was righting his table. While getting up, he was wiping the gravy and contrasting yellow corn from his OD green uniform.

Two F-4 Phantom jets had dropped their air-brakes on the dive to the Tay Ninh runway, which caused the excessive high-pitched squeals. Their afterburners reverberating off the concrete runway when they turned skyward did the rest.

Once everyone realized what had happened, there was no laughter. I can still remember watching some of the disgusted (depressed?) crews continue to sit on the floor. It was almost pathetic. They were going to finish eating their chicken or anything from lunch they could salvage.

Fifty years ago, this was NOT funny.

Now, it is one of my fonder memories.

August Appendix:

FYI: I think it is interesting after reading the following report that no one I know who flew this day remembers being interviewed by the accident investigation team. I certainly was not. The gunner, RA Huff is not listed on our 187th AHC unit roster and the crew chief Dugan (same name but different spelling) has not been found either.

Fortunately, after an extensive search, I made contact with Harold Greer the co-pilot on 65-12669. His synopsis and corroboration are at the end.

Helicopter or incident 65-12869

Accident Investigation Report:

Information on U.S. Army helicopter UH-1D tail number 65-12869

The Army purchased this helicopter 0966

Total flight hours at this point: 00001749

Date: 08/30/1968

Accident case number: 680830081 Total loss or fatality Accident

Unit: 187 AHC

The station for this helicopter was Tay Ninh in South Vietnam

UTM grid coordinates: XT748163

Number killed in accident = 0 . . Injured = 8 . . Passengers = 5

costing 228554

Original source(s) and document(s) from which the incident was created or updated: Defense Intelligence Agency Helicopter Loss database. Army Aviation Safety Center database. Also: OPERA (Operations Report. )

Loss to Inventory

Crew Members:

AC MAJ RJ FOLTA

P CPT HE GREER

CE DUGAN

G E4 RA HUFF

Passengers and/or other participants:

LTC E KEESLING, PAX, D

MAJ TF SCHATZMAN, PAX, D

CPT W KELLY, PAX, D

1LT JG COAN, PAX, D

E9 TW DAVIS, PAX, D

Accident Summary:

The aircraft was engaged in a command and control mission. The mission started on 30 Aug 68 at 0600 hours, and at approximately 1500 hours, the crew changed aircraft at Cu Chi because of an oil leak in the generator; taking the alternate command and control ship. After refueling at Cu Chi and taking off with it's flight at approximately 1715 hours, the command and control ship proceeded to XT 501194, in the vicinity of Trang Bang. There the slicks went in to pick up troops on the ground while the command and control ship orbited for about 10 minutes. The flight then proceeded down route 1 toward Camp Cu Chi to intercept route 8A. At 1500 feet on the southeast corner of Camp Cu Chi, the transmission pressure warning light came on, and the aircraft commander announced over the intercom that their transmission oil pressure had dropped to zero. The aircraft commander asked the crew chief if the gages had shown any malfunction in the past to which the crew chief replied in the negative. The pilot then asked the aircraft commander if they should not go into Cu Chi, as they were on a downwind for landing at the staging area. The aircraft commander elected not to land at Cu Chi but to continue on with the mission, monitoring the transmission temperature gage. The flight continued on at approximately 1300 feet along route 8A to the landing zone. The pilot was monitoring his altitude closely and staying close to route 8A in case of a forced landing. The command and control ship arrived east of the LZ and Fire Support Base Crocket and had turned to a northerly direction to watch the insertion of the troops to their left (west). At this point a loud noise was heard in the transmission, the aircraft turned left and the nose pitched up, dissipating forward airspeed and rotor RPM. The pilot and aircraft commander put the aircraft in autorotation while the aircraft commander called a may day. The aircraft continued to spin to the left, sinking at a rapid rate. The aircraft commander was able to level the aircraft and pull in little remaining pitch just prior to impact in a rice paddy. The impact caused momentary unconsciousness to the aircraft commander and pilot. The crew chief noticed that the engine was still running so pulled the main fuel and start fuel switches to off, and turned off the battery.

This record was last updated on 04/17/1997

Harold Greer’s narrative:

“We had been flying as I recall 12 plus hours by then. When that transmission light came on, we both caught it. I had controls as C&C command and Maj Fulda [Fulta] were managing the final insertion. I brought the altitude down from 2500 ft to 1500. When the aircraft suddenly jarred sideways, it took both our total efforts to control it. And as quickly the transmission locked, it again broke free. How the rotor blades just didn’t shear off is by the grace of god. As Gorecki taught me, it was left pedal and dive and as the rice paddy came at us like a roller coaster hitting bottom it was all safety reaction and we pulled remaining collective. The Gorecki trained dive and the rice paddy splash saved our lives and you guys did the rest as we always did for each other. I remember you coming after us and telling us you were breaking formation. It was too easy to just fall out the open door sides as the crew chief yelled fire. But none of us as could raise up as we all had compression joint fractures. I remember the troops you were carrying setting up a security perimeter. And your crew chiefs dragging each of us away from the aircraft to safety while also grabbing cryptic books. You all had to leave us but Chu Chi based Medivac was quick to recover us. Next day, Maj Gaffney was immediate to see us and I remember vividly his facial expression as my body went back into shock. That was the last occasion I saw anyone from our unit. But I quickly learned we were the lucky one of so many badly wounded or dying in the Camp Zara Japan General Hospital. While recovering in Japan, I asked to return to the 187th thinking recovery was near term. We were a unit of brothers that risked our lives daily for each other and all those young soldiers we supported. We grew up wat to fast and saw the horrors of war. Never to see any unit brothers again until Springfield, IL gathering, I understood why all are absolutely great Americans that joined, served, left the Army and prospered as American professionals.

. . . And thanks for coming and getting me. You saved our lives.”

FYI: Harold recovered and spent a career in the Army. He was medically retired after three major back surgeries and ended his service as a Lieutenant Colonel.

Thanks again Harold for adding valuable information to this story

Pat

1968 Vietnam as an RLO © (Sept 1968)

(September 1968)

Joseph P Dougan

Published Jun 8, 2022

September was a forgettable month … or, maybe I should say in my drug-induced state because I don’t remember much about it. 😊 Heroin/Marijuana laced drugs didn’t make their official appearance to me until my second Vietnam tour in 70-71, so this absence of memory was all prescription-induced. I spent much of September sick because I developed pneumonia. Tay Ninh is 22’ above sea level, and the dirt is fine silt. Lung infections can get out of hand quickly. My infection became a bad case because I waited too long to have it checked out. We were short pilots which contributed to my poor judgment and not seeking treatment sooner.

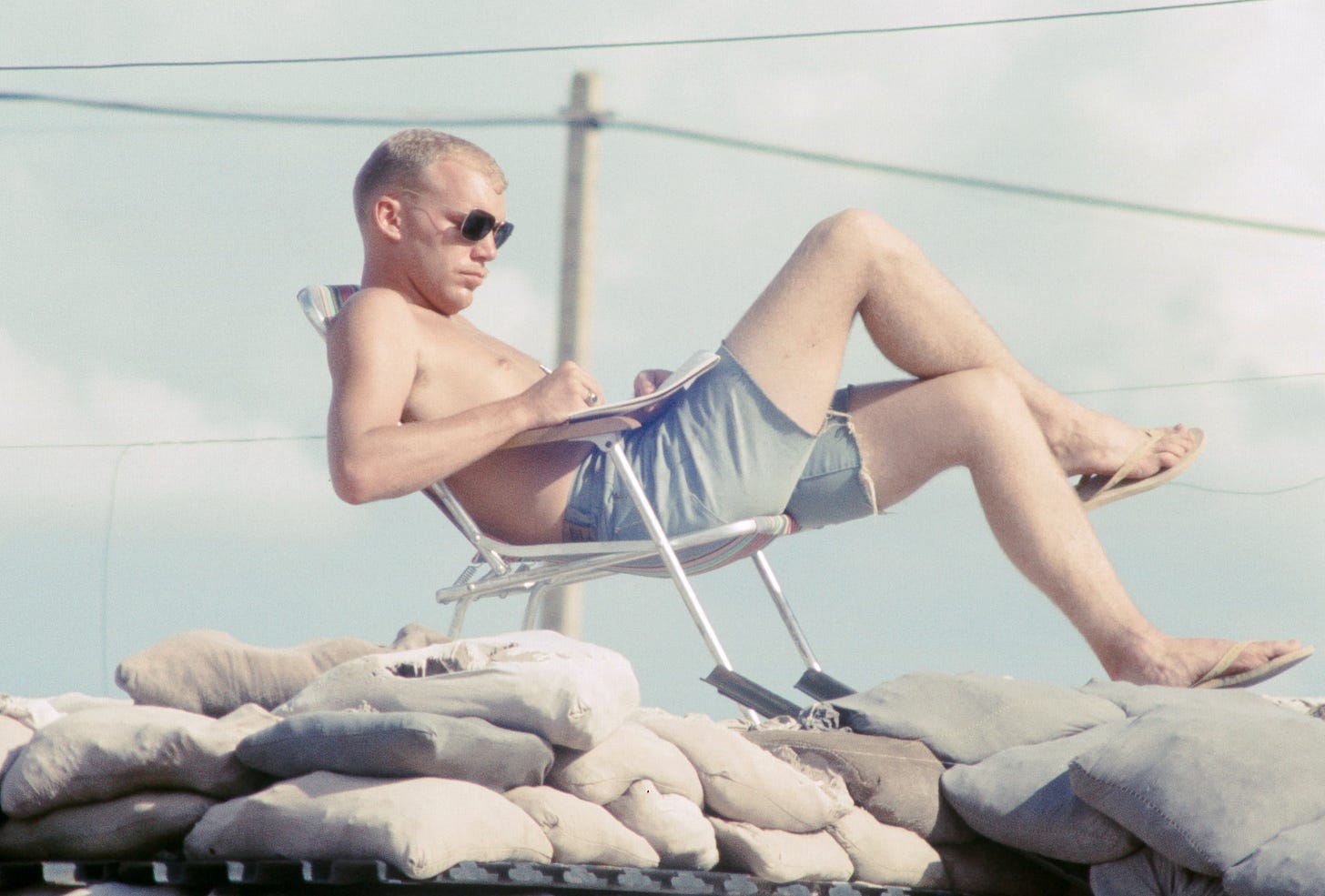

The flight surgeon grounded me for about ten days. I spent virtually all of my recovery time sitting in the hot sun on the dispensary patio. Following the doctor’s orders, I drank massive quantities of orange juice and took meds accompanied by a lot of vodka. I am not sure the vodka was on the original Rx. 😊 For that matter, I don’t remember much about that month, so who knows what the doctor really said.

Pneumonia Recovery … who said codeine and alcohol don’t mix?

While convalescing, turtles started arriving. I am not sure how that term was coined; turtles were our newbie replacements. Perhaps it was because when you first get to Vietnam you keep your head tucked below your shoulders, waiting for something bad to happen. Usually, the really bad things happened when they had their heads stuffed up in their rectal cavity, but I digress. Four or five RLO’s showed up at about the same time. One of these RLO’s would have to be my platoon’s replacement Crusader 16. The Warrant Officer pilots would become platoon members.

From Slicks to Guns

There was a certain mystique being in the Rat Pack, the moniker of our gun platoon. I had not been allowed to transfer there because of the Date of Rank issue that I mentioned in a previous chapter. Dan Vogle, the gun platoon leader, had twenty-four hours date of rank over me, and the CO, Major Gaffney, was concerned there could be a conflict.

I like being in charge, and he knew it too well. 😊

The Rat Pack was going to lose its core of experienced fire team leaders as many team leaders would be leaving Vietnam within thirty days of each other in November and December.

The fire team leader in the gun platoon often became an adjunct C&C directing the flights, especially on short-final (approaches) to the LZ’s. The remaining Rat Pack pilots were neither experienced enough with company flight operations nor had the situational awareness to be promoted to a team lead position. That is no reflection of their flying abilities; it was an experience and judgment issue. They would develop in time, but they weren’t ready yet.

It was determined that the DOR between Dan and I would not be a problem, and it became for me a priority to get into the Rat Pack to train before the experienced team leaders went home. My transition started by sharing time between the two platoons. I learned the armament systems in one and worked with the new RLO’s leading the flights in the other.

When I officially moved, Dan and I became roommates again.

There was never a conflict.

Fire Mission, Over

October through November would become an intense flying period for me. In addition to making immediate assessments of the new RLO’s for a possible platoon, section leader, and flight lead assignment, I had to start my gunship transition, now.

C-Model (Charlie models) Hueys look similar to the H-Model slicks to the uninitiated, but they differ significantly in their construction and flight characteristics. H-Models are designed for maximum lifting and interior space for infantry carrying capacity. The C-Model has a uniquely different rotor system designed for maximum maneuverability, and the cargo area is small. If you are familiar with horses, the differences in flight would be like transitioning from a Tennessee Walker to a fully trained cutting horse. Or, if you prefer cars, a four-door sedan to a sports car.

The H-model Huey is designed for lifting -- a C-model, not so much 😊. The excess weight from the external armament systems and ammunition often made C-models challenging to get off the ground, especially after taking on a full load of fuel. Regardless, “If it will hover, it will fly.”

However, most gunship pilots never believed you could have too much ammunition, so takeoff weight and hovering were always issues. Pilot technique played a key role in safe Charlie model operations. Once airborne and streamlined, gun teams became the cowboys racing their steeds around at treetop levels dodging trees, often lead arrows, looking for the “Indians” while reconnoitering an area. Leading the flight of slicks into an LZ would require us to be back at altitude providing suppressive fires.

The indigenous native’s area of operation (Indian-Country) 😊 had another name, a “Free-Fire Zone.” Our situation maps outlined these areas which were updated daily for known enemy activity. Any Vietnamese seen in a free-fire zone were targets, not people. There would be no friendly forces in the area i.e., shoot anyone on sight; they are the enemy. I’ll rehash my first exposure to a free-fire zone, covered in another story from earlier this year.